This blog post is a continuation of a previous post.

“What about the alt-left that came charging at, as you say, at the alt-right? … You had a group on one side that was bad. You had a group on the other side that was also very violent.” – Donald Trump

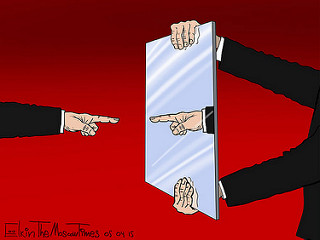

This was a particularly disappointing moment in a press conference on Wednesday this week where Trump was taking questions about the violence in Charlottesville, VA. His response here is a classic example of “Whataboutism,” and it is something that we need to recognizing in our own speech. It is getting in the way of us having meaningful conversations with each other and moving forward on issues like racial reconciliation.

Whataboutism, is a diversionary rhetorical strategy that is known by a number of different names: The Appeal to Hypocrisy Strategy, The False Equivalency Argument, ( or by it’s fancy Latin name “tu quoque” which means “you too”) It is a shutdown move that ends the possibility of dialogue about the issue at hand. If you and I are in disagreement and you respond to my challenge with “but what about ______” you are not addressing the issue I brought up. You are charging me with being a hypocrite: “What right do you have to bring this up when you are guilty of that.” It effectively ends the conversation and makes it impossible to move forward.

Whataboutism, is a diversionary rhetorical strategy that is known by a number of different names: The Appeal to Hypocrisy Strategy, The False Equivalency Argument, ( or by it’s fancy Latin name “tu quoque” which means “you too”) It is a shutdown move that ends the possibility of dialogue about the issue at hand. If you and I are in disagreement and you respond to my challenge with “but what about ______” you are not addressing the issue I brought up. You are charging me with being a hypocrite: “What right do you have to bring this up when you are guilty of that.” It effectively ends the conversation and makes it impossible to move forward.

If we want to be part of the solution and not part of the problem, if we want to move forward on matters of significance we need to recognize poor use of language and learn how to respond to things like whataboutisms more effectively.

A couple days ago a friend posted an article written by Matt Walsh talking about the violence in Charlottesville. You can read it here.

Walsh condemns white nationalist marchers and Nazi sympathizers in clear and concise terms, but then he steps off the curb and commits a whataboutism.

…There are those who want to pretend that the Nazi terrorist coward who got in his car and plowed through a crowd on Saturday did something unprecedented. Sadly, that is not the case. Have we already forgotten about the Black Lives Matter march in Dallas that ended with five Dallas police officers being executed in the street? Or the many hundreds of police officers and journalists and citizens who’ve been beaten or pelted with rocks at leftist “protests”?

This is another classic appeal to hypocrisy strategy. It immediately draws the conversation into a debate about which side is more evil? Which is more guilty? Which was more violent? All the while we have forgotten what we were previously talking about. I continue to be amazed at how quickly the “Black Lives Matter” movement gets dragged into conversations about what happened in Charlottesville.

Black Lives Matter has nothing to do with this.

An appeal to hypocrisy is something we do when we are afraid to have a hard conversation. We need to stop letting people in our lives derail a chance to have a meaningful discussion about painful issues.

So let’s do this. I have been wanting to write a blog post about Black Lives Matter for a couple of years and have been afraid to do it. The reason it is so hard to talk about is that we get derailed by whataboutisms before we can really get started. Let’s look at what a positive conversation might look like:

The Black Lives Matter movement was formed in 2012 after seventeen-year-old Trayvon Martin was murdered while walking in his own neighbourhood by George Zimmerman, who was later acquitted for his crime. Stories eerily similar to this one have played out repeated since then. Dozens of young black men have shot and killed by law enforcement officers who were later acquitted of any wrong doing.

The Black Lives Matter movement was formed in 2012 after seventeen-year-old Trayvon Martin was murdered while walking in his own neighbourhood by George Zimmerman, who was later acquitted for his crime. Stories eerily similar to this one have played out repeated since then. Dozens of young black men have shot and killed by law enforcement officers who were later acquitted of any wrong doing.

And that is usually about as far as we get in this conversation. At this point we are often derailed by a whataboutism. “But what about what he was doing? Where was he headed? Was he wearing a hoodie? Don’t all lives matter?” Then the conversation dissolves into an argument about which side is more right? Or which side is less wrong? In the end, an opportunity to have a conversation has been lost.

It doesn’t have to be this way. One of my professors from school posted a great piece last week where he wrote about Dietrich Bonhoeffer’s opposition to the Nazi party (and to the state church) in 1934. He said,

When Dietrich Bonhoeffer basically said “Jewish Lives Matter” in 1934, he was not saying “No Other Lives Matter” but was identifying a systemic problem within the culture and its use of power.

Of course, “all lives matter.” At the same time, circumstances sometimes demand we state just as resolutely “the lives in this group matter” because the lives in that group are threatened in systemic ways by those in power and with power–some of those ways are embedded in how power is used by some (not all or even most) within the system.

This does not mean all activities or tactics of the “Black Lives Matter” Movement are good, just, or righteous. What it does mean, however, is “Black Lives Matter.” And there is a real and authentic reason for concern when those in power undermine that truth, whether by neglect or intent.

Here with the Black Lives Matter example, we bailed on the conversation before we could talk about the systemic injustice of the law enforcement system in Canada and the United States. We never got to have a converation with substance because we were too afraid to hear it. It takes courage to talk about a system where black males are three times as likely to be shot by police.

It takes courage to face the fact that, despite drug use between blacks and whites being the same, black males are 6 times more likely to be arrested for drug crimes. Blacks are five times more likely to be incarcerated than whites. Why is that? In the US there are now 2.2 million people of all colours in prison. The United States makes up about 5% of the world’s population and has 21% of the world’s prisoners. Why? If we want to make this world a better place, if we want to start solving problems like race relations we are going to have to find a way to listen to each other (I’ll say more about that tomorrow)

A friend of mine once shared a phrase that often helps awkward conversations go better. When someone comes at you with something that is hard to hear–maybe they are sharing their opinion with you and you strongly disagree. Instead of using a whataboutism to shut down the conversation, try this: say, “Say more.”

Invite your conversation partner to share how they came to that opinion. Why do they think what they do? It is possible that, although you don’t agree, you might be able to understand their opinion a little better if they could share more about how they feel. At the very least it would increase the probability that they feel heard and you might be able to find something that the two of you could do to address the problem.

The way forward on matters like race relations is through tough conversation, something I’ll say more about tomorrow.

NCW

Pingback: Taking a Stand Against Racism is a Meaningless Gesture | ephesians2eight

Pingback: “Nobody Was Born Racist” and other Things I Wish Were True | ephesians2eight